Oh dear.

It seems Gene Roddenberry’s zipper, if not the Starship Enterprise he imagined, had a gravity problem. It was constantly down.

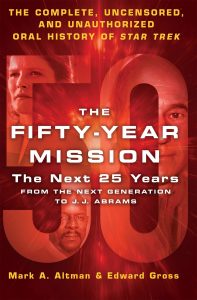

Unless you’ve been stranded on a lonely planet in a far distant galaxy, you know it was the 50th anniversary of Star Trek the other day, having first aired on September 8, 1966.  A new book, The Fifty-Year Mission is described in NRO as a “two-volume, 1,300-page oral history documenting the history of the franchise… an extraordinary achievement of research and reporting, filled with inside scoop and backstage drama, fragile egos and the surmounting of great technical challenges… essential for diehards, as well as for readers interested in film and television production in general.” Now, clearly, as described, the book is multifaceted & comprehensive, but, naturally, it’s Roddenberry’s horn-dogginess that’s getting the headlines.

A new book, The Fifty-Year Mission is described in NRO as a “two-volume, 1,300-page oral history documenting the history of the franchise… an extraordinary achievement of research and reporting, filled with inside scoop and backstage drama, fragile egos and the surmounting of great technical challenges… essential for diehards, as well as for readers interested in film and television production in general.” Now, clearly, as described, the book is multifaceted & comprehensive, but, naturally, it’s Roddenberry’s horn-dogginess that’s getting the headlines.

The aforementioned NRO article, titled The Great Boor of the Galaxy is a worthwhile read for a Trekkie, but below are a few select paragraphs. Enjoy.

No one is more responsible for this sense of novelty than Star Trek’s creator, Gene Roddenberry, whose posthumous reputation more closely resembles that of a religious figure than a Hollywood producer. With his long hair, sideburns, and bushy eyebrows, his professorial clothing and theatrical sense, Roddenberry in his maturity took on the appearance of his friend Isaac Asimov, instructing generations of adoring fans in the tenets of IDIC, or “Infinite Diversity in Infinite Combinations,” a philosophy of logic, inquiry, multiculturalism, and peace.

Roddenberry is lauded as a progressive icon, a prophet, the self-styled “Great Bird of the Galaxy” directing humanity to a limitless future in the stars. “There is no question in my mind that Roddenberry is a genius,” says actress Diana Muldaur. “There’s no disputing his genius,” says movie producer Harve Bennett. “He was a man who was able to reach out through my television and explain to me that I had a place in the world and in the future,” says Whoopi Goldberg. Longtime Roddenberry friend and collaborator Bob Justman is more measured but just as complimentary: “His background was very humble, but he’s a man who educated himself and he’s found that his mind is fertile ground.”

…

But there is a problem. Intended as a tribute to Star Trek and its creator, The Fifty-Year Mission ends up debunking the Roddenberry mythos. Liberal visionary? Maybe. But he was also an insecure, misogynistic hack.

…

Roddenberry never stopped rewriting. “The problem,” says his biographer Joel Engel, “was that he basically couldn’t write well enough to carry it off.” For 25 years, a script never left Roddenberry’s hands without becoming worse.

For all of the control Roddenberry exercised over Star Trek, the franchise prospered only when it was under the aegis of others… The Star Trek that has imprinted itself on fans for decades is Gene L. Coon’s. His shows deepened the relationships between Captain Kirk, Mr. Spock, and Dr. McCoy. He created the Klingons. There was more humor. Says writer David Gerrold, “Gene L. Coon created the noble image that everyone gives Roddenberry the most credit for.” Shatner puts it this way: “Gene Coon had more to do with the infusion of life into Star Trek than any other single person.”

With Coon at the helm Roddenberry turned to other projects, and to his own worst instincts. He was a horn dog. Affairs with police secretaries had been just the start. While on the force he had become friends with Jack Webb, the star and producer of Dragnet, who eased his entry into Hollywood and competed with him for the affections of actress Majel Barrett. Meanwhile Roddenberry also had an affair with the actress, singer, and model Nichelle Nichols. His relationship with Barrett was an open secret, lasting a decade before he divorced his wife. He and Barrett got married in 1969. (Their son, Rod, was born in 1974.) As for Nichols, Roddenberry cast her in a history-making role as Star Trek’s Lieutenant Uhura.

…

The episodes Gene L. Coon supervised are considered to be Star Trek’s finest. But Coon did not last long. When Star Trek recaptured Roddenberry’s attention, he didn’t like what Coon had been doing. And Coon, who had grown tired of arguing with Roddenberry, Shatner, and Nimoy, was out.

…

Roddenberry died in 1991. You could argue that the franchise he created has been more successful in the 25 years following his death than it had been in the 25 years before…

…

It was the brilliance of the idea, and the psychological need it satisfies in audiences, that allowed Roddenberry to get away with being, in most respects, an incredible, insufferable jerk to his family, friends, and peers. After reading The Fifty-Year Mission, I know why Gene Roddenberry stuck so fiercely to his notion of a future where human nature has been transformed into pure good. It’s because he knew more than anybody how truly awful we can be.

### end ###